A free template for keeping track of your pre-tenure achievements

Build a strong tenure file from day one

Blog Categories

I'm a certified coach and associate professor of philosophy at the

University of San Francisco

Hey, I'm Becca

The ultimate guide to service for pre-tenure faculty

Feeling in the dark about service?

5 must-read books for pre-tenure faculty

Filed under:

9 minute read

It probably goes without saying, but there is a lot about being a professor that you don’t learn in graduate school. Feeling like a fish out of water (despite having spent 10+ years living and breathing university life) is completely normal. But if you’d like to feel a little more like you know what you’re doing (by the way, you’re doing great!), these five books are a good place to start.

Maybe you’re already thinking: “How will I have time to read FIVE books on top of everything else I’m doing?”.

Fair enough.

My recommendation is to pick the book that speaks to your greatest need right now. Read that one.

Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less by Greg McKeown

What this book is about

McKeown argues that instead of trying to balance a growing list of projects and tasks, we can have greater success and more happiness by doing less in an discerning and disciplined way.

His argument is structured as a contrast between two archetypal characters: the “Essentialist” and the “Nonessentialist.” Nonessentialists think that every task and opportunity is important, and are constantly trying to find ways to fit it all in.

Nonessentialists react to whatever is most pressing in the moment, say “yes” unreflectively, and end up taking on too much. As a result, their lives feel out of control and they are constantly overwhelmed and exhausted. By contrast, the Essentialist believes that only a few things really matter. Rather than trying to do it all, they embrace the reality of trade offs. Instead of reactively doing whatever happens to demand their attention, Essentialists pause to discern what really matters, and say “no” to whatever that doesn’t make the cut. Unlike Nonessentialists, Essentialists feel in control of their work and their lives, and can therefore enjoy those opportunities they carefully chose to pursue.

McKeown’s assumption is that most people are Nonessentialists; his thesis is that being an Essentialist is a better way to work and live. His book is an instruction manual for how to give up the way of the Nonessentialist, and embrace the way of the Essentialist.

Most of the anecdotes and examples in the book are drawn from McKeown’s corporate milieu, but his advice has far-reaching relevance. Many of the Nonessentialist characters he describes have clear academic counterparts, and most faculty could benefit from adopting a more Essentialist perspective on their research, not to mention teaching and service.

Why pre-tenure faculty should read it

Getting tenure is difficult, and many elements of the process are fickle and unfair, but it is not a game of 10-dimensional chess. At most colleges and universities, only two types of work matter for tenure and promotion: research and teaching. Although faculty are expected to do service (e.g., committee work, peer review, advising), this part of the job plays a negligible role in tenure and promotion decisions.

Moreover, research is more important than teaching. Having abysmal teaching evaluations might prevent you from earning tenure, but, at many institutions, if your publication record is strong (whatever that means at your institution and for your discipline), you can earn tenure while being a mediocre teacher. However, without a strong publication record, having stellar teaching evaluations (and a teaching award, and glowing letters from former students, or from colleagues who have observed your teaching) isn’t enough.

Now, this is not an argument for being a bad teacher or abstaining from service. But if your institution cares the most about research for tenure and promotion, then research should be your priority (singular). Not being an outstanding teacher (by pouring hours and hours into lesson planning and one-on-one meetings with students). Not being the Leslie Knope of professional citizenship (by performing extensive service to your department, university, and profession).

Devoting most of your time and energy to research (some on teaching, and very little on service) is the way of the Essentialist.

Even if you are not spending too much time on teaching and service, pre-tenure faculty often have far too many research “priorities” (if everything is important, then nothing is), or their priorities are out of alignment with their tenure and promotion criteria (e.g., you agreed to write a chapter for an edited volume when your institution really only cares about publications in high-ranking, peer reviewed journals).

McKeown’s book will teach you how to think differently about priorities: how to identify them, and how to avoid the trap of the “trivial many” which misdirect and diffuse your time and energy away from the activities that matter most for tenure and promotion.

The No Club: Putting a Stop to Women’s Dead-End Work by Linda Babcock, Brenda Peyser, Lise Vesterlund and Laurie Weingart

What this book is about

Babcock, Peyser, Vesterlund, and Weingart argue that, across industries—including academia—women are disproportionately asked and expected to do “non-promotable” work: that is, work that matters to your organization but will not help you advance your career. At most universities, advancement is based on research and teaching, not service. Therefore service tasks (e.g., reviewing the curriculum, hiring new faculty, reviewing applications to graduate programs, hosting an alumni event etc.) are non-promotable. Multiple studies show that women tend to do more of them than men (and women of color do much more).*

For example, at one large, state university, untenured women faculty accounted for 60 percent of untenured faculty on faculty senate committees, even though only 38 percent of untenured faculty were women. As Babcock, Peyser, Vesterlund, and Weingart observe, “this made their service load two and a half times that of their male junior colleagues” (58).

The authors uncover systematic gender disparities in non-promotable work, describe its effects on women in concrete terms, and analyze the structural dynamics which produce the unequal division of non-promotable labor. They also provide concrete advice on how to ensure you’re not doing more than your fair share of non-promotable work, how to say “no” to requests to perform it, and how organizations can reduce non-promotable work disparities.

Why pre-tenure faculty should read it

If you’re a woman faculty member on the tenure track, you need to know what you’re up against: you will be asked to do non-promotable work more often than your male colleagues, and you will be expected to say “yes”, and you may face backlash if you say “no”. This book will teach you how to say “no” in a way that avoids negative repercussions (I wrote about some of these strategies here), and how to advocate for yourself and other women faculty at your institution.

I really, really, really wish I had this book as a pre-tenure faculty member.

Write No Matter What: Advice for Academics by Joli Jensen

What this book is about

The central argument of Jensen’s book is that faculty research productivity requires frequent, low-stress contact with writing projects we enjoy. She provides actionable strategies to help faculty achieve this relationship with their research.

Why pre-tenure faculty should read it

For most faculty, writing is not low stress. Even if you had a supportive PhD advisor (and many graduate students don’t), it’s stressful to write while worrying about finishing the dissertation and finding a decent academic job. You’d think that securing a tenure-track faculty position would take some of the pressure off, but it definitely doesn’t. Now you just have more to do in addition to trying to meet unclear expectations under significant time pressure. This environment is not conducive to writing.

Jensen’s book will help you to find calmer writing waters amidst the pre-tenure storm. Her book preaches a new perspective on being an academic writer (the “craftsman attitude”), and identifies common writing myths (for example, the belief that you need to take care of all of your other obligations, or read “one more source” before you can start writing) that cause faculty to abandon ship before they even start. If you’re eager to stem the tide of writing anxiety and get your research in shipshape, Jensen’s book will show you the ropes (with fewer nautical metaphors

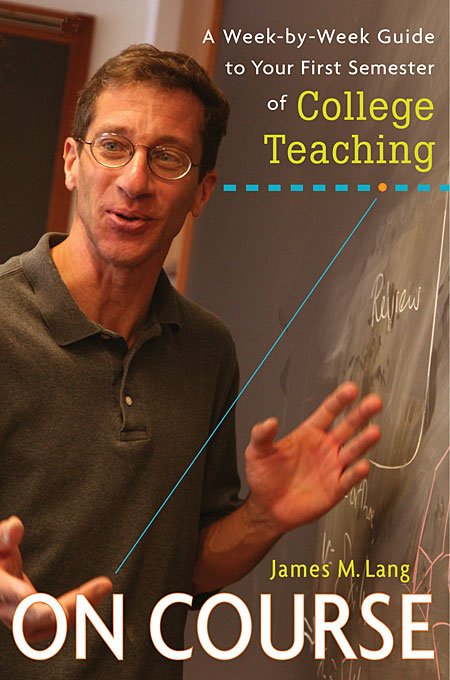

What this book is about

The title pretty much says it all. It has chapters on creating a syllabus, lecturing (fun fact: in a 50-minute lecture, students are attentive to the lecturer around 40 percent of the time), facilitating discussions, teaching with small groups, assignments and grading, re-energizing a lethargic classroom, and common problems (for example, rude and disorderly student behavior, laptops and cell phones, absenteeism and tardiness, fear of public speaking). On Course is not a comprehensive overview of teaching and learning theory, or a complete compendium of pedagogical practices. It is aimed at professors with little or no teaching experience who want to know how to get through their first year of teaching.

Why pre-tenure faculty should read it

As I explain here, only two types of work matter for tenure and promotion at most colleges and universities: research and teaching. Some pre-faculty gain teaching experience in graduate school, or after they graduate as adjuncts. But many start their first year of college teaching having never designed a course and taught it from start to finish.

You can get tenure without being an outstanding teacher (research is more important even at many institutions that genuinely value teaching), but you would probably be less stressed if you knew a bit more about how to do the second-most-important aspect of your job. Lang’s book contains pretty much everything you need to know as a new professor and then some.

Do I love the cover image? No. Should you read it anyway? Yes.

I Will Teach You To Be Rich by Ramit Sethi

What this book is about

This book is everything you need to know about saving, investing, paying off debt, and spending wisely. For Sethi, teaching you to be rich isn’t about teaching you how to become a millionaire (though he can help you with that). Instead, your “rich life” is what you want it to be: maybe that’s being able to afford a full-year sabbatical at 75% salary, retiring by age 60, or paying off your student loans.

Sethi’s advice comes with a fair amount of sass, but as the son of immigrants (who frequently gets accused of being a “communist” on social media for his progressive politics), he is on a mission to help ordinary people understand their finances, and to learn how to save and invest without lining the pockets of bankers, financial advisors, and wealth managers. (He really, really hates Wells Fargo and is on the Bank of America’s “negative influencer” list.)

Why pre-tenure faculty should read it

When I started my job as an assistant professor at the University of San Francisco, it was the first time I even thought about doing anything with my money other than paying rent and buying groceries. I had been living paycheck to paycheck and hand to mouth for years and years as a graduate and undergraduate student.

Though money was tight at first (the cost of living in the San Francisco Bay Area is extremely high), my faculty job came with retirement benefits and I was dimly aware that I ought to be saving for the future. The problem was, I had no idea how to go about doing that.

I suspect many pre-tenure faculty are in roughly the same boat. After years of earning poverty wages as a student or postdoc, many new faculty have not learned the basics about saving and investing.

Fortunately, my hair stylist recommended Sethi’s book to me and it taught me everything I needed to know about personal finances. My husband and I followed his easy, six-week program, and started saving for retirement, emergencies, and, someday, a house.

tl;dr

If you’re feeling in over your head as a new professor, here are five books that can help you find your bearings:

-

To learn how to establish priorities: Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less by Greg McKeown

-

To learn when and how to say “no”: The No Club: Putting a Stop to Women’s Dead-End Work by Linda Babcock, Brenda Peyser, Lise Vesterlund and Laurie Weingart

-

To write more consistently: Write No Matter What: Advice for Academics by Joli Jensen

-

To learn the fundamentals of college teaching: On Course: A Week-by-Week Guide to Your First Semester of College Teaching by James M. Lang

-

To learn the basics of personal finance: I Will Teach You To Be Rich by Ramit Sethi

*The authors note that there is little to no data on non-binary faculty.